This guest article is written by Tim O’Brien and Claire Clifford of INTO University Partnerships, where Tim serves as Senior Vice President for New Partner Development and Claire as Vice President for Pricing, Insights and Research.

A Wall Street Journal piece published on June 4, 2025, highlighted that international students contribute over US$40 billion annually to the US economy. The report also referenced speculation around possible restrictions on Optional Practical Training (OPT)—a program that allows international graduates to gain vital professional experience in the US.

Meanwhile in the UK, the government has signaled its plan to reduce the Graduate Route work visa from two years to just 18 months. Findings from our recent research show that these policy shifts could weaken the foundation of global student mobility. What was once perceived as an additional advantage has become a core element in making overseas study financially sustainable.

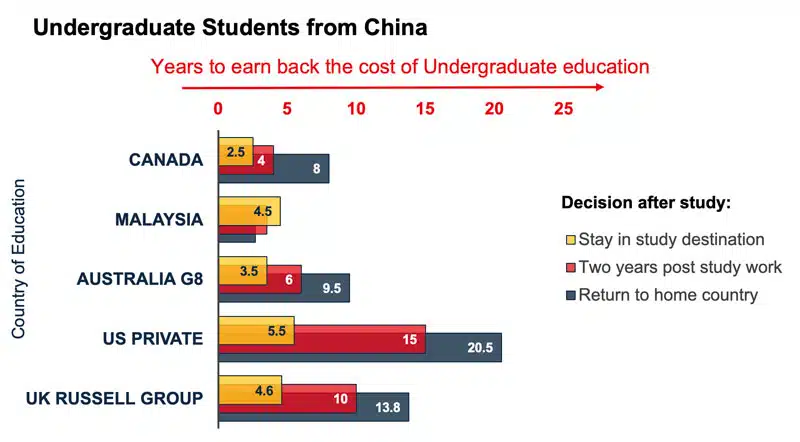

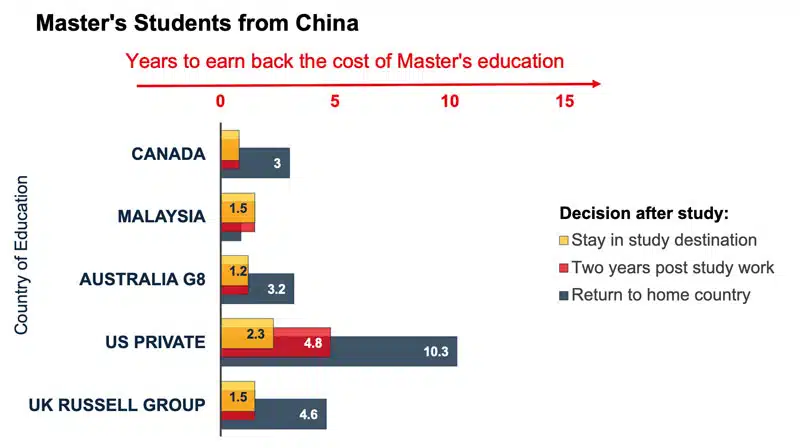

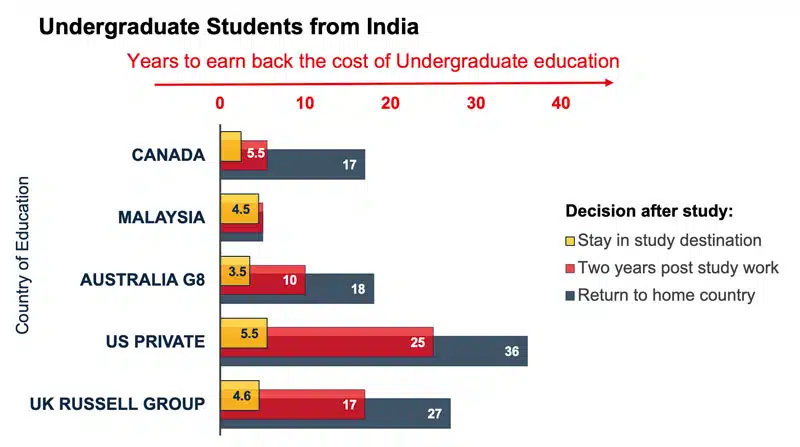

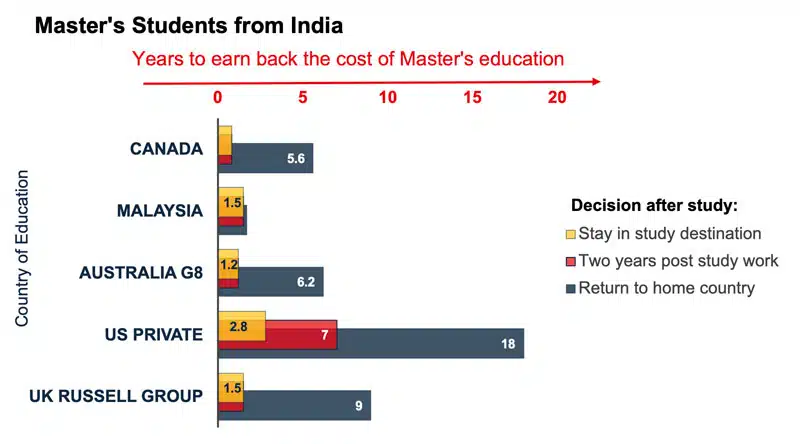

Take the example of an Indian student completing a bachelor’s degree at a US private university: without work rights, it could take more than three decades to recover the financial outlay. With just two years of post-study employment, the repayment timeline shrinks by 11 years—and in Canada or Australia, it can be reduced to as little as three. For Chinese students, access to post-study work opportunities can shorten the payback period by nearly six years. (These projections use average graduate earnings in each country and account for standard taxation.)

In every scenario, the data points to the same conclusion: post-study work options significantly accelerate the return on investment, making them not only attractive but essential for students and their families.

China

As the first chart illustrates, a student who graduates in the UK and returns directly to China would face a repayment period of nearly 14 years to cover the full cost of a three-year undergraduate degree at a Russell Group university, including living expenses. With the option of two years of post-study employment, that burden is reduced by about four years. For master’s students, the picture is similar: returning immediately means it takes around 4.6 years to recover the cost of a one-year master’s program, but engaging in post-study work in the UK can cut that time by nearly half.

In another scenario, if the same undergraduate secures a graduate-level role in the UK before heading back home, the repayment window shortens even further—by almost five years—bringing the breakeven point down to just under four years.

India

The data also shows that Indian students who return home right after completing a three-year undergraduate degree at a Russell Group university would need nearly 14 years to earn back the full cost, including living expenses. Choosing a non-Russell Group institution shortens that timeframe by about two years. For master’s students, the recovery is quicker, with the cost of a one-year program being recouped in just under five years if they return home immediately.

If, however, an undergraduate secures graduate-level employment in the UK before heading back, the repayment timeline drops significantly—by more than eight years—allowing them to break even in just five and a half years.

But affordability cannot rest solely on the shoulders of immigration policy. While reducing tuition may not be financially sustainable, universities must innovate in how they deliver programs. Offshore campuses, hybrid learning, and transnational degree structures enable students to begin their studies locally at lower cost and complete them abroad, still gaining the global experience and qualifications employers prize.

These alternatives are expanding quickly. As Dr. Cheryl You wrote in Times Higher Education, “More students are opting for in-country pathways, such as foundation programmes or 2+2 joint degree arrangements between Chinese and Western universities, as more practical and supportive alternatives. In addition, they are increasingly looking beyond traditional overseas study destinations to closer-to-home alternatives, such as Hong Kong, Macao or elsewhere in Asia.”

When it comes to post-study work rights, they remain central to the value proposition of international education. Such opportunities are not about permanent migration, nor do they strain public resources. In the UK, for instance, international graduates on post-study work visas contribute through additional surcharges for access to the National Health Service. Crucially, short-term work experience abroad makes a world-class education more financially viable for students, while supplying host countries with much-needed skills—particularly in high-demand sectors like technology and other knowledge-driven industries.

For both universities and policymakers, the conclusion is unavoidable: a student’s return on investment has become the defining measure of trust in global higher education. Student mobility thrives when the financial equation makes sense for all parties.

Methodology note: Calculations are based on average tuition and living costs across destination countries, paired with graduate starting salaries (after tax) under three different post-graduation scenarios.

Source: https://monitor.icef.com/2025/08/how-post-study-work-rights-can-make-or-break-the-return-on-investment-for-study-abroad/